Does Europe have any magic left?

Local support has been crucial to the development of Europe’s leading ecosystems and companies

In the early 1980s, a pioneering group of 70 researchers at the Catholic University of Leuven (KU Leuven), in Belgium’s Dutch-speaking Flanders region, had an ambitious plan. Their aim was to launch a microelectronics research and development (R&D) ‘superlab’ and propel a new chip-based industrial revolution.

But the aspiring researchers required substantial funding to make their dream a reality. “We needed to make significant investments in advanced equipment, which would have been difficult for the university to fund by itself,” says Luc Van den hove, who joined the researchers group as a 24-year-old PhD student working in electrical engineering.

Luc van den Hove, CEO and president of imec. Image via imec.

Luc van den Hove, CEO and president of imec. Image via imec.

In 1984, the imec was established as a spin-off from KU Leuven, thanks to a €62m initial investment from the regional Flemish government. The non-profit organisation has since become one of the world’s most important “independent” electronics R&D centres. It is home to thousands of researchers and a pilot production line with about $4bn-worth of complex semiconductor-making equipment.

Today, imec stands at the heart of an ecosystem of companies that, over the years, have leveraged their partnership with imec to develop world-leading technologies. They feature the likes of ASML, the only firm in the world that owns the technology to produce microchips out of silicon wafers and whose machines are used by every major advanced semiconductor producer.

“If you want to be leading in the world, you need to work with the best possible companies, wherever they are,” says Mr Van den hove, who became imec’s president and CEO in 2009. imec’s business and financing model enables it to be a neutral provider of R&D services in the semiconductor industry, which is otherwise intensely competitive and fraught with geopolitical rivalry.

Bird's eye view of imec in Leuven, Belgium. Image via imec.

Bird's eye view of imec in Leuven, Belgium. Image via imec.

imec is the prototype of European brilliance: global-class talent planted its seeds in Leuven, creating a platform for academics, industry players and local policy-makers to join forces and innovate. Locations across Europe have repeatedly tweaked this triple-helix approach according to the needs of their researchers and entrepreneurs, setting the foundation for some of the continent’s most consequential, albeit often unsung, stories of economic development success.

Their trajectories tell a story of a continent whose innovation drive, while lacking the frenetic pace of the venture capital (VC)-fuelled US tech scene, continues to breathe new life into Europe’s post-industrial societies, shaping models of development that are often replicated across the globe.

Europe now faces a reckoning with the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and its role in the new global order hangs in the balance. While the regionalisation of supply chains may bring back industries and jobs, high energy prices weigh on the continent’s competitiveness. Besides, many of the firms in the process of reorganising their production base are being lured into looking overseas by the siren song of very assertive incentives from the White House in strategic, emerging industries.

A September 2022 report by the McKinsey Global Institute said that Europe “needs to act decisively to develop and scale competitive firms and technologies more quickly” for the sake of long-term resilience and prosperity.

Yet the unsung stories of European brilliance reveal a pattern others can follow to drive development, create the industry leaders of tomorrow and, eventually, defy perceptions of an old, declining continent.

Devolution and deregulation

Imec’s path from university spin-off to a world-leading electronics R&D hub was helped by a confluence of factors including its neutrality, operational efficiency and cost-sharing model. However, the catalyst for its foundation in Leuven was helped by generous funding and clear vision from the regional Flemish government.

Constitutional reforms in Belgium over the 1970s and 1980s helped transform the small country from a unified state into a federal system, with different communities, regions and language areas. These reforms gave autonomy to the Flemish government in areas including the economy, international trade, innovation, culture and education.

Joy Donné, the CEO of Flanders Investment & Trade, the region’s development agency, tells fDi that a local “third industrial revolution” policy in the 1980s aimed to boost Flanders’s knowledge base and potential to innovate, with a particular focus on the renewal of local industrial ecosystems in new materials and microelectronics.

“Close collaboration was successfully stimulated between universities, research institutes and industry to drive technological advancements and support the growth of technology-based business,” he says.

Joy Donné, the CEO of Flanders Investment & Trade (FIT). Image via FIT.

Joy Donné, the CEO of Flanders Investment & Trade (FIT). Image via FIT.

In the 1980s, financial support from the Flemish government made up the majority of imec’s budget. Today, the annual government grant accounts for less than 15% of imec’s budget, with the majority made up by local and international contract research with industry.

Paul Van Dun, the head of the technology transfer office at KU Leuven, explains that while imec maintains close working relationships with local universities and professors, its independent hierarchical management structure has been crucial to its success.

“If you want to cater for broad framework contracts with global leading companies like Intel, Samsung, Philips or ASML, you need a top-down organisation with a clear direction,” he adds. “This is a very tough task within a university.”

KU Leuven’s Central Library

KU Leuven’s Brugge Campus

A reform that devolved education and science policy to Belgium’s regions was particularly important to the development of Leuven’s ecosystem, according to Koenraad Debackere, the executive director of R&D at KU Leuven.

“They made science and innovation a spearhead of Flemish policy,” he explains. “The ecosystems that are thriving today are where the knowledge institutes, which are most often universities, understand they have a role to play in helping create the conditions in which activities can thrive.”

This devolution of power paved the way for tech transfer activities at KU Leuven, according to Mr Debackere, as they enabled universities to own intellectual property rights and participate in seed funds investing in start-up companies based on university research.

In 1972, KU Leuven became one of the first European universities to set up a technology transfer office, which helps commercialise research. Mr Van Dun says that back then, closer relations between university and industry “was not paid as much attention to as today”, but has become a fundamental part of local economic development policy.

This is indicated by the capital flowing into companies being spun out from university research. Global funding for university spin-outs in 2021 reached a record figure of just under $41bn, up by 76% on the previous year, according to Global University Venturing, a market intelligence and publishing company. Despite the market pullback and macroeconomic pressures, 2022 was still the second-highest year for university spin-out funding at $25.4bn.

‘The Cambridge Phenomenon’

Links between university and industry are at the roots of some of Europe’s most successful ecosystems. In the English city of Cambridge, a change to the local university’s policy towards industry in the 1970s led to the creation of Cambridge Science Park, a meeting place for innovative companies and university researchers, and the first of its kind in Europe. The origin of Cambridge’s innovation ecosystem, which today attracts among the highest VC funding per capita in Europe, is often attributed to this openness to industry and loosening of local planning regulation.

The Lakeside Cafe at The Bradfield Centre, one of several buildings within Cambridge Science Park, an innovation centre established in 1970. Image by kind permission of Trinity College, Cambridge and Cambridge Science Park.

The Lakeside Cafe at The Bradfield Centre, one of several buildings within Cambridge Science Park, an innovation centre established in 1970. Image by kind permission of Trinity College, Cambridge and Cambridge Science Park.

“There was a proliferation of activity from that point onwards,” explains Tomas Ulrichsen, the director of the University Commercialisation and Innovation Policy Evidence Unit at the University of Cambridge. The conducive research environment in Cambridge has attracted big name companies like Microsoft, IBM, Huawei and the global headquarters of pharmaceutical giant AstraZeneca.

In what has been dubbed ‘the Cambridge Phenomenon’ — the transformation of a small market town into a global technology hotspot — world-leading platform technology companies have emerged in areas such as life sciences, artificial intelligence and quantum computing.

“A number of institutes and units have been set up in Cambridge to support the translation of ideas, engagement with industry and students to become entrepreneurs,” says Mr Ulrichsen. “Success breeds success.”

Europe-wide innovation

From Portugal’s Lisbon in the west to Lithuania’s Vilnius in the east, Europe’s capitals are home to numerous highly sophisticated innovation ecosystems. Indeed, Europe has attracted more foreign investments into R&D activities than any other global region, according to fDi Markets figures dating back to 2003. Last year broke records, with more than 670 R&D projects worth over $12.8bn announced by foreign investors across Europe.

Unsurprisingly, larger innovation ecosystems in Europe take the lion’s share of foreign direct investment (FDI) into R&D activities. London, Dublin, Paris and Barcelona have attracted more than 160 FDI projects each since 2003, collectively accounting for around 10% of Europe’s total number of foreign R&D investments.

But it is often smaller, less well-known ecosystems that are home to companies that are indispensable to the global value chains of strategic industries. A case in point is in semiconductors: while the vast majority of global chip manufacturing capacity is in east Asia, many higher-value added activities are undertaken in relatively unknown European locations.

From Portugal’s Lisbon in the west to Lithuania’s Vilnius in the east, Europe’s capitals are home to numerous highly sophisticated innovation ecosystems. Indeed, Europe has attracted more foreign investments into R&D activities than any other global region, according to fDi Markets figures dating back to 2003. Last year broke records, with more than 670 R&D projects worth over $12.8bn announced by foreign investors across Europe.

Unsurprisingly, larger innovation ecosystems in Europe take the lion’s share of foreign direct investment (FDI) into R&D activities. London, Dublin, Paris and Barcelona have attracted more than 160 FDI projects each since 2003, collectively accounting for around 10% of Europe’s total number of foreign R&D investments.

But it is often smaller, less well-known ecosystems that are home to companies that are indispensable to the global value chains of strategic industries. A case in point is in semiconductors: while the vast majority of global chip manufacturing capacity is in east Asia, many higher-value added activities are undertaken in relatively unknown European locations.

Netherlands-based ASML, which formed as a spin-off from electronics giant Philips in 1984, has a global monopoly over the production of extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography machines. These huge, sophisticated machines are used by the likes of TSMC and Samsung to produce the world’s most cutting-edge microchips.

imec has collaborated closely with ASML on research since the company’s inception. “You can’t fabricate an advanced chip without European technology,” explains Mr Van den hove, adding that Europe is home to leading companies in sensors, power electronics, micro controllers and has leading manufacturing capabilities in these areas.

At ASML’s headquarters in Veldhoven, a small town 90-minutes’ drive from Leuven, the company employs more than 14,000 people — equivalent to nearly one third of the town’s total population. Despite recent local opposition to ASML’s planned facilities expansion, the company has fuelled local economic development.

Several of ASML’s crucial suppliers are European, too. Carl Zeiss, a company headquartered in Oberkochen, a German town of just 8000 people, is the only manufacturer of the precise mirrors and lenses used in EUV machines. Another German manufacturer, Trumpf, supplies the laser systems used in these same machines.

There are also prominent chipmaking ecosystems in Europe, such as Silicon Saxony, a cluster of around 2500 companies across the IT supply chain in eastern Germany. Silicon Saxony accounts for one in every three chips made in Europe, and includes the semiconductor factories of GlobalFoundries, Infineon and Bosch. US-based chipmaker Intel announced in March 2022 that it would invest €17bn into two new fabrication plants in the nearby city of Magdeburg. In Saarland, a state in south-western Germany, US chipmaker Wolfspeed announced plans in February 2023 to invest $3bn into a new chip manufacturing facility.

Netherlands-based ASML, which formed as a spin-off from electronics giant Philips in 1984, has a global monopoly over the production of extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography machines. These huge, sophisticated machines are used by the likes of TSMC and Samsung to produce the world’s most cutting-edge microchips.

imec has collaborated closely with ASML on research since the company’s inception. “You can’t fabricate an advanced chip without European technology,” explains Mr Van den hove, adding that Europe is home to leading companies in sensors, power electronics, micro controllers and has leading manufacturing capabilities in these areas.

At ASML’s headquarters in Veldhoven, a small town 90-minutes’ drive from Leuven, the company employs more than 14,000 people — equivalent to nearly one third of the town’s total population. Despite recent local opposition to ASML’s planned facilities expansion, the company has fuelled local economic development.

Several of ASML’s crucial suppliers are European, too. Carl Zeiss, a company headquartered in Oberkochen, a German town of just 8000 people, is the only manufacturer of the precise mirrors and lenses used in EUV machines. Another German manufacturer, Trumpf, supplies the laser systems used in these same machines.

There are also prominent chipmaking ecosystems in Europe, such as Silicon Saxony, a cluster of around 2500 companies across the IT supply chain in eastern Germany. Silicon Saxony accounts for one in every three chips made in Europe, and includes the semiconductor factories of GlobalFoundries, Infineon and Bosch. US-based chipmaker Intel announced in March 2022 that it would invest €17bn into two new fabrication plants in the nearby city of Magdeburg. In Saarland, a state in south-western Germany, US chipmaker Wolfspeed announced plans in February 2023 to invest $3bn into a new chip manufacturing facility.

Entrepreneurial relevance

While global-class research has been the trigger for the rise of major innovation centres such as Leuven and Cambridge, Europe’s entrepreneurial spirit is also second to none. From Venice merchants in the Middle Age to the British engineers of the industrial revolution in the 18th century, European history is deeply intertwined with the origins of global trade and industry. The trajectory of European manufacturing peaked in the 1980s, when factories started moving to cheaper destinations in east Asia and elsewhere. Often troubled and marred by pockets of unemployment, the transition to post-industrial societies left much legacy talent on the ground.

With the global economy quickly evolving and incorporating new technologies and geopolitical borders, a new cohort of European entrepreneurs are turning that legacy talent coming from established, but ailing, local industries into a new frontier of European innovation.

One standout country in this regard is Sweden, which has emerged as a centre for electric vehicle batteries thanks to the plans of Northvolt, a local start-up founded in 2016. The Northvolt-driven development of the battery supply chain in Sweden has effectively maintained Swedish relevance in the automotive industry; it is a large contributor to the country’s exports and employs about 140,000 people.

Peter Carlsson was the former head of supply chain at Tesla until 2015, when he returned to his home country to co-found Northvolt. He convinced several industry heavyweights to join him, including another former Tesla executive Paulo Cerruti, and Yasuo Anno, a stalwart of Japan’s battery industry. While other European battery start-ups have failed to get off the ground or gone into administration, such as Italvolt and Britishvolt, the success of Northvolt is widely attributed to Mr Carlsson’s clout, and that of his experienced senior colleagues.

Peter Carlsson, the CEO of Northvolt and former head of supply chain at Tesla. Image via Northvolt.

Peter Carlsson, the CEO of Northvolt and former head of supply chain at Tesla. Image via Northvolt.

“Northvolt was the first serious, truly European challenger and was able to attract large numbers of foreign experts,” says Bo Normark, an industrial strategy executive at EIT InnoEnergy, a sustainable energy consultancy, training provider and early investor in Northvolt. Today, the battery start-up has raised more than $7bn in funding, according to Crunchbase, employing more than 3000 people across Europe.

Northvolt’s original plan was to build Europe’s largest gigafactory for lithium-ion batteries in Sweden with an annual production capacity of 40 gigawatt-hours (GWh) and research facilities in a single location. Instead, the company decided to build a gigafactory in Skellefteå, a former mining town in northern Sweden with abundant hydropower; and an R&D campus and demonstration facility in Västerås, a city of 160,000 people located 100km west of the capital Stockholm. Northvolt’s plans, which include another gigafactory in Gothenburg with local automotive player Volvo have enabled Sweden to attract upstream battery value chain companies in areas like separator film, foil and casings.

Electricity hub

Mr Carlsson, who serves as the company’s CEO, said in a October 2021 statement that “establishing a campus where industrial actors can engage, surrounded by all necessary facilities ... can create the necessary foundation for Europe to emerge as the leading region for [battery] technology”.

While Västerås is not a large vehicle production hub like Gothenburg and Stockholm, it has been able to leverage its historic expertise in electrical generation and applications. The city is home to global research hubs for companies like French train manufacturer Alstom and electrical equipment giant ABB, which was formed in 1987 through the merger of local Swedish company ASEA and Swiss company BBC.

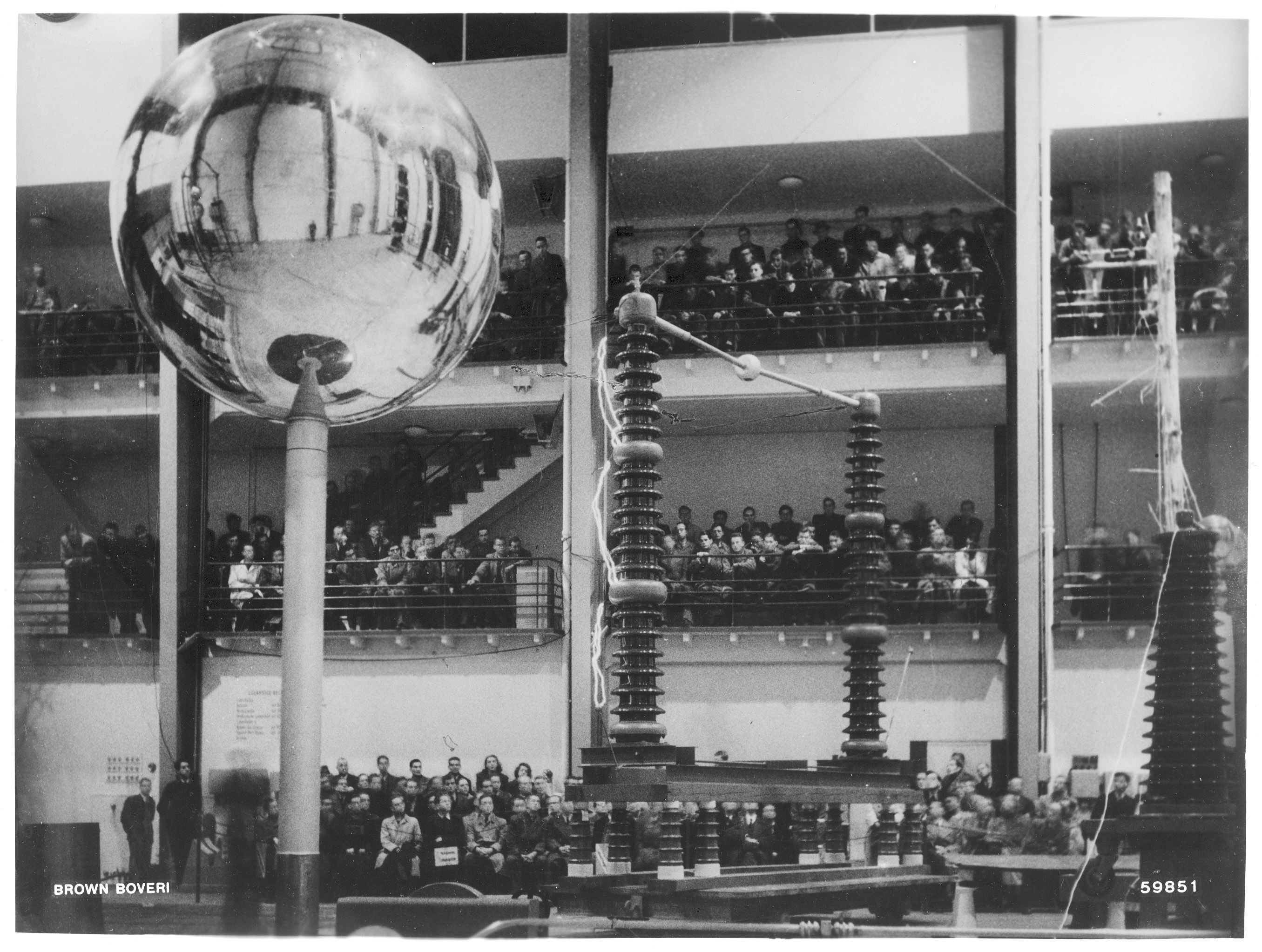

High voltage laboratory demonstration in 1943. The Swedish-Swiss electrification and automation company ABB was formed by the merger in 1987 of BBC and ASEA, a company founded in Västerås. Image via Historisches Archiv ABB Schweiz.

High voltage laboratory demonstration in 1943. The Swedish-Swiss electrification and automation company ABB was formed by the merger in 1987 of BBC and ASEA, a company founded in Västerås. Image via Historisches Archiv ABB Schweiz.

Torbjörn Bengtsson, the director of investment promotion at Invest Västerås, explains that close collaboration between the city, politicians and local industry players like ABB in Västerås made Northvolt’s project possible.

“Västerås has been able to leverage its ecosystem of building everything for electricity generation, distribution and batteries,” he says. “A few years back, the industrial sector was focused on cost cutting and moving to central Europe and Asia. Northvolt has been instrumental in changing that mindset.”

Mr Normark of EIT InnoEnergy says that the initiative from Northvolt “created an avalanche in Europe” to build up the battery value chain through strategic partnerships. The European Battery Alliance, an industrial development programme launched by the European Commission in 2017 and spearheaded by EIT InnoEnergy, has helped drive these efforts to develop the battery value chain through partnerships.

Several other European locations have become hubs for the battery industry. This includes Hungary, where Chinese battery giant CATL is set to invest more than €7bn into Europe’s largest gigafactory with a capacity of 100 GWh.

Decentralised engagement

If Sweden’s legacy automotive and electrical components industries proved a major source of knowledge and skills for Northvolt to develop a local battery industry from scratch, Switzerland’s history of reformism, innovation and global financial institutions provided South African entrepreneur Johann Gevers with all the good reasons to start his new venture in the Alpine country.

In May 2013, Mr Gevers was looking for a crypto-friendly location to move his cryptofinance start-up Monetas. Having decided against moving to Silicon Valley due to the US government’s opposition to cryptocurrencies, Mr Gevers narrowed down his options to three locations: Singapore, Lichtenstein and Switzerland. “Crypto technologies are fundamentally about decentralisation,” he explains. “If I was going to make an investment, I needed to reduce my risk and find a location with a decentralised culture, political and legal system.”

Johann Gevers, the founder of Crypto Valley. Image via Johann Gevers.

Johann Gevers, the founder of Crypto Valley. Image via Johann Gevers.

The decision was made to move to Switzerland, due to its citizen-controlled political system, business friendliness and history of innovation. Mr Gevers says that at the time “Switzerland needed to reinvent itself”, as it was experiencing money outflows after the international community had clamped down on Swiss banking secrecy.

In July 2013, Mr Gevers moved his company to the Swiss town of Zug, where he found the authorities take a “totally different approach” to other cantons in Switzerland. “They did not offer me any special favours or incentives,” he explains. “What attracted me was that it’s a level playing field for everyone.”

Zug, the heart of the Crypto Valley. Photo by Peter Wormstetter on Unsplash

Zug, the heart of the Crypto Valley. Photo by Peter Wormstetter on Unsplash

Today, Zug is the heart of the Crypto Valley, a sweeping ecosystem spanning from Zürich to Liechtenstein, which is home to more than 1100 blockchain companies. Mr Gevers says the openness of Switzerland’s authorities, including the financial regulator Finma, to work with the industry to shape crypto-friendly regulations has been crucial to the ecosystem’s development.

In neighbouring Liechtenstein, there is a similar openness to blockchain technology and its applications. In October 2019, Liechtenstein became the first nation in the world to regulate the ‘token economy’, enabling all assets and rights to be tokenised using blockchain technology and bringing certainty to an otherwise unregulated area.

The regulatory regime was drafted through a small public–private working group of cryptocurrency experts including Mr Gevers and Thomas Nägele, a software developer and lawyer who advises international financial institutions on blockchain technology.

“In finance, legal clarity and certainty is crucial for innovation to happen,” says Thomas Dünser, another member of the working group and the director of the Liechtenstein government’s Office for Financial Market Innovation.

Mr Nägele agrees, noting that by implementing some of the most comprehensive crypto regulation in the world, Liechtenstein has attracted multiple companies seeking legal certainty about their operations.

“It is better to think about the regulatory approach before there are bad cases,” he says. “If you don’t take enough time to understand the technology, you’re going to kill a huge potential for innovation.”

Opportunistic development

The need to address the challenges stemming from the transition to post-industrial societies is behind another stunning story of European economic development success.

In February 2012, a local councillor named Michał Jędrzejek in the small Polish city of Katowice took a chance. In the mid-1990s, Katowice had closed coal mines in and around the city, and hoped to drive its post-industrial revival. Mr Jędrzejek was a fan of competitive video games (esports), which were then relatively unknown in economic development circles but just beginning to take off as an industry.

He sent an opportunistic message to Michał ‘Carmac’ Blicharz, who at the time was the director of Pro Gaming for ESL, a German esports organiser and production company behind the Intel Extreme Masters (IEM), the world’s longest-running pro gaming tour.

“Is there a chance to organise an IEM in Katowice?”, wrote Mr Jędrzejek, having read that IEM had outgrown its venue at the CeBIT computer conference held in Hannover, Germany. The response from Mr Blicharz, that “there is always a chance”, would transform the city’s economic prospects.

Today, the IEM is now synonymous with Katowice. Following the success of the first event held in the Spodek arena in 2013, it has grown to become a magnet for economic activity and investment. By 2019, IEM Katowice attracted about 174,000 attendees and had become the largest esports expo in the world.

Taiwanese esports team Flash Wolves lift the trophy after winning the IEM Katowice World Championship for League of Legends in 2017. Photo by Helena Kristiansson via ESL Gaming.

Taiwanese esports team Flash Wolves lift the trophy after winning the IEM Katowice World Championship for League of Legends in 2017. Photo by Helena Kristiansson via ESL Gaming.

“Katowice has become the ‘Mecca’ of esports and gaming,” says Sebastian Weishaar, president of esports at ESL Faceit Group, the organiser of IEM Katowice. “The city has created a visibility in our industry that is unheard of in probably any other discipline on such a global scale. If people from China, America, Brazil and all over the world have an affiliation with our industry, Katowice really means something to them.”

ESL Faceit Group has also invested into the city to support the event. In 2020, the company built an 8000 square metre production hub with five large studios. It employs more than 150 people and supports esports events around the world.

Marcin Krupa, the mayor of Katowice, tells fDi that IEM is an important part of the city’s promotion strategy in domestic and international markets and has benefited local hotels, restaurants and entrepreneurs servicing the event.

Esports fans queue outside the Spodek arena in Katowice. Photo by Helena Kristiansson via ESL FaceIT Group.

Esports fans queue outside the Spodek arena in Katowice. Photo by Helena Kristiansson via ESL FaceIT Group.

Companies including US tech giant IBM, consultancy PwC and Japanese IT multinational Fujitsu have all set up offices in the city since the event was started. The city is currently building a gaming and technology hub in the now-closed coal mine of Wieczorek, aiming to further develop the momentum created by the event.

Katowice is an example of how “steady image building enables municipalities to take advantage of the snowball effect”, Mr Krupa explains. “This event has been so successful that its implementation and costs are never questioned by either the residents or the opposition in the city council.”

The story of Katowice is an echo of how leveraging new industries can boost post-industrial urban development. This was popularised by the Spanish city of Bilbao, which reignited its local economy through the development of the Guggenheim, an arts and cultural institution.

Europe’s recipe for global relevance

Given Europe’s relatively well-educated workforce, strong public institutions and modern infrastructure, it is no wonder that there are examples of companies and ecosystems that are world leading.

Since 2014, the EU has encouraged locations to pursue smart specialisation strategies for regional development to access cohesion policy funding. This approach involves devolving the task of picking winners and setting R&D investment priorities to local regions, rather than at the European level. Its aim is to reduce regional disparities and create more world-leading ecosystems and homegrown champions.

“Smart specialisation is an attempt to reverse the ongoing process of de-industrialisation and backshore manufacturing capacity in key industries away from emerging markets, and in particular China, to the EU,” explains Angela Wigger, an associate professor of global political economy at Radboud University in the Netherlands.

While it aims to support European locations' movement up transnational value chains, Ms Wigger says the policy has the potential to exacerbate structural inequalities due to competition between more advanced and less advanced regions: “It is not an appropriate strategy for alleviating structural disparities.”

Nonetheless, the proactive support from local authorities in places from Flanders in Belgium to the Polish city of Katowice, have led to some of the most prominent locations for innovation across Europe. A focus on place-based collaboration between industry and universities and regional decision-making has helped foster some of Europe’s leading champions.

Despite wide-ranging narratives about regionalisation and the decline of Europe vis-a-vis other global regions, Mr Van den hove of microelectronic hub imec is unequivocal about the specific strengths of the old continent: “Europe is globally relevant and has strong opportunities to stay globally relevant.

“There will be a lot of dependencies globally. The world is changing at rapid speed. We just have to make sure we further strengthen the strengths of Europe and collaborate based on those strengths.”

Further reading on Europe

European Cities and Regions of the Future 2022/23

This ranking compares the most promising investment destination across Europe. Across Europe, much of 2022 was overshadowed by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and its reverberations across the continent. However, data from fDi Markets paints a resilient picture.